How to better deal with your emotions

(≈11min read)

Have you ever noticed that your mind has a mind of its own?

You’re driving along, a smile on your face, the sun shining bright, when out of nowhere the car in front of you comes to a sudden stop. Slamming your foot on the breaks, your body hurtles into the triangular embrace of your seatbelt. Looking up, you breathe a sigh of relief – mere inches away from a collision.

And then it begins; those waves of rage begin to circulate through you; every inch of your body feels as if it’s on fire. You desperately want to scream out at the top of your lungs, tell that stupid driver ahead just how useless and incapable they are. But your kid in the backseat holds you back. You tell yourself that anger is pointless, that being mad won’t change the situation, that the best thing to do is to remain calm.

But the more you try and suppress it, the madder you get. And for the rest of the day, that feeling doesn’t leave; you’re not yourself, impulsive, snappy and still frustrated by a random stranger you’ve never and will likely never again meet.

So the question is: how could you have dealt better with your anger?

Well, first off, it’s interesting to note that the rational portion of your brain didn’t ask for that anger to be there; it in a sense bubbled up from a deeper more primitive part. William Irvine, professor of philosophy, uses the ‘roommate analogy.’

He suggests that living with this primitive subconscious mind that provides intrusive thoughts is like having a roommate who keeps telling you what you should think, want and feel. A living nightmare.

You might succeed to get the roommate to shut up for a bit but soon they’ll be right back at it, making new suggestions. If you actually had a roommate like this, not only would you lose your sanity, but you’d presumably move out if they refused to negotiate. The problem is, you and this roommate are stuck together in your skull until your very last day on Earth.

You need to devise a strategy to deal with this roommate situation because exercising willpower to shut up your roommate constantly is too exhausting.

The aim of this article is to provide you with tips so you can learn to cultivate a better relationship with this roommate and realise that although they can tell you what emotions to feel, you don’t have to listen. You don’t have to take ownership of the thoughts or feelings this roommate provides. The idea is that by using the rational part of the mind you can better deal with the sub-rational part.

ACT

ACT, or in full, acceptance and commitment therapy, is a form of psychotherapy that encourages people to embrace their thoughts and feelings rather than fight or feel guilty about having them. Anytime we actively repress an emotion or a thought, it’ll usually come back stronger and more powerful. Picture pulling back an elastic band, and then releasing it.

We therefore need an alternative. ACT proposes we should simply acknowledge the existence of these powerful emotions and allow them to naturally pass, realising they don’t control us.

Addiction and anxiety, for example, are both heavily dependent on thoughts, primarily faulty thoughts, keeping them alive. By practising ACT and reinforcing the idea that your emotions have no bearing on your actions, it can help you to feel more liberated from your mind. This, in turn, should help on your quest to become a more emotionally stable individual.

Negative emotions, just like positive emotions, serve a functional purpose; they are resources we can use to understand how our brain is feeling. Rather than categorising emotions into ‘bad emotions’ and ‘good emotions’ and trying to ‘push away’ the bad ones, ACT pushes the idea that we should instead see all our emotions as useful tools rather than uncomfortable inconveniences.

In this article, I’m going to summarise the key points of ACT, as well as exploring other ways we can learn to better deal with our emotions.

Emotions do not control us

The first thing to acknowledge is that emotions do not control our behaviour. We can feel sad and yet smile at all those around us. We can feel angry yet display calmness. The exterior is not necessarily indicative of the interior.

Take a minute to imagine yourself casually strolling through the woods, when you encounter a bear. Your natural instinct tells you to run, to sprint away. But if you do, it will trigger the bear’s pursuit response and you’ll be its dinner. So instead, when your body is trembling, when your heart is thumping like it’s going to explode out of your chest, you need to remain calm. You need to overcome that primal feeling of fear and slowly edge away, always facing the bear, in order to escape.

There is a direct comparison here to emotions in general. Although you can’t control your emotions (just like how in the bear scenario there is no way to remove that feeling of fear), you can still learn to manage them. Remembering that they do not control you is the first step.

Happiness is not about feeling good

There are so many people who live under this delusion that the way to deal with negative emotion is to simply attempt to remove all negative feelings entirely and instead ‘feel good all the time’.

But if happiness were just a matter of feeling good, drug users would be amongst the happiest people on earth. There’s a huge difference between living a life predicated on meaning and purpose and a life where there’s reliance on short term gratification to sustain health and wellbeing.

Author of ‘The Happiness Trap’, Russ Harris says:

“So here is the happiness trap in a nutshell: to find happiness, we try to avoid or get rid of bad feelings, but the harder we try, the more bad feelings we create.”

A natural progression from ‘I need to feel good’ is ‘I must not feel bad’. This leads to something known as experiential avoidance where your main goal is to simply avoid all potential painful feelings. Sounds good on the surface of things, but this mind-set turns out to be insanely damaging. It strips you not just of pain but also of joy.

Often, things that you’re initially anxious about, you end up actually really enjoying and you never would have experienced that joy, if you’d have been completely discomfort avoidant. You can’t have love without fear of rejection (unless you’re a supermodel). You can’t achieve great things without fear of failure. By removing the possibility of pain, you are simultaneously removing the possibility of joy.

Instead of living your life based on running away from anxiety and all these negative things, try to run towards the things you do want and learn to cope with those negative emotions along the way.

Coping with negative emotion

The basic principle of ACT is that any attempt to push away negative emotion will likely result in more negative emotion. When you try and repress emotions and thoughts, you’re not exactly solving the problem at hand – repression is exhausting and draining and ultimately pointless.

Why? Well because when you eventually don’t have the mental energy to push those emotions away anymore, they’ll come back stronger.

As opposed to trying to control our emotions, ACT suggests we should learn to simply acknowledge the fact that we don’t have as much control over our emotions as we’d like. That might sound like a weird thing to acknowledge; to imply we can’t really control our emotions.

But the emphasis here is not on ‘control’ but on acknowledging the fact that emotions have virtually no power over us. We can learn to simply experience the raw sensations that emotions give without allowing them to alter our behaviour in any way.

An example: let’s say you frequently tell yourself that you’re not good enough and this always triggers a negative emotional response. Now instead of simply saying ‘I’m not good enough’ to yourself, instead say:

“I’m having the thought that I’m not good enough”

By adding the ‘I’m having the thought that’, you are in a way, making the active choice to dissociate your thoughts from you. It’s just a thought, just some words in the back of your mind that may or may not be correct and may or may not be useful or helpful.

You don’t want to try and repress that thought but instead acknowledge it until it passes on, like a dark stormy cloud passing by in the sky, and then return to whatever it is you are doing. The more you practise, the better you’ll get. Practising meditation and mindfulness techniques can also help.

You are learning, to outline a Buddhist idea, for your thoughts “to become like robbers in an empty house”. They cannot affect you or hurt you or take anything away from you. You should instead view your thoughts as a kind of consistent and constant background radio noise. You don’t try and ignore this noise; you just let it play and don’t pay much attention to it.

Instead you can tune in for the helpful thoughts and just allow that blur to continue for the unhelpful ones. In the roommate analogy, instead of listening to everything your mental roommate says, you can instead acknowledge that he/she is saying something but realise he/she may or may not be right.

Most importantly, whatever your roommate is saying doesn’t need to affect how you behave; he/she has no power whatsoever. You are in control of your actions.

Comparison

You’ve probably heard it a million times, but a great deal of suffering and emotional distress comes from when we compare ourselves to others. When you play the comparison game and base your self-worth on other people, you’re setting yourself up to lose.

No matter how good looking you are, there’ll always be someone who looks better. No matter how smart you are, there’ll always be someone who’s smarter. No matter how good you are at anything, you’ll always be able to find someone who your brain can use to justify your own inadequacy.

Social media doesn’t exactly help with this. So many of us wake up, automatically reach out to grab our phone and as we aimlessly scroll, our mind absorbing all this amazingness and talent seemingly oozing from every other person around us, we, lying frozen in bed, can’t help but to compare ourselves to them, can’t help but to think of ourselves as a failure, as ‘not enough’.

Social media glamorises others to the point where you can easily start to believe that normal average broken people are simply deficient of any real flaws or weaknesses. You’re not exactly going to get many people who’d be content posting a sub-par picture of themselves, and so all you’re left with is the good stuff, all those pictures that took half an hour to perfect.

You’re also imbued with this distorted sense of reality which encourages you to believe that you’re the only person not working ten hour days or writing a novel or blogging daily or starting up a business. But what you’re comparing yourself to is nothing but a highlight reel.

What someone posts online is not a representation of them. Behind the screen and the glamour, they are a normal person who feels pain and suffers and feels that same empty, vacuous void in the pit of their stomach as you.

I get that it’s hard to accept but when you start to put your needs first and think more about what you want rather than how what you are doing compares to others and how it might make you look, you’re increasing the odds of you feeling more content.

In general, the only person you should be comparing yourself to is your past self. When you start becoming reliant on likes or follows to make you happy, you’re just subjecting yourself to a perpetual feeling of deficiency – no matter how many likes or followers you have, you could always have more.

If you’re content with whatever it is you’re doing, irrespective of others, then that should be enough. You shouldn’t need pats on the back for your achievements. You shouldn’t do things just to impress others. As I note in my ‘life list’, a pretty good way to determine whether a goal you’re striving for is a goal that you truly want is by asking yourself the following question:

“If I were not allowed to talk to anyone ever about this goal after I achieve it, would I still be doing it?”

If the answer is yes, then that means you want to do this thing for you and nobody else. A no, on the other hand, indicates the goal is motivated by how you want to be perceived by others.

Honesty

Although this might seem like a super weird method to better deal with emotion, there is something to be said about striving to become more honest. I know the link between honesty and emotional stability might feel tenuous, but when you really consider the implications of lying, it becomes apparent just how negatively it could impact your emotional wellbeing.

Now I’m not talking about lying to your partner about their clothes looking good; I’m talking about a deeper kind of lie – the lie we tell people about who we really are. There’s a tendency for each of us to hold up a mask, a veil in front of our own face and act in ways around other people solely because we want to be perceived in a certain way. It’s human nature to want recognition, praise and respect.

But these desires are in many cases the root of emotional instability.

As I’ve discussed earlier, the more you repress a certain emotion, the worse it’ll become.

Wearing a mask constantly is draining and exhausting and when that mask inevitably falls off, you’ll find you begin to plummet, and fast. Imagine filling up a balloon. The more you hold in those emotions, the more you’re pumping that balloon with air. The problem is, one day the balloon’s going to pop.

Learning to be honest about who you are and being able to express exactly what you genuinely feel to other people is a kind of superpower. You’re not forced to be anything you’re not; no having to conceal anything or repress anything; you’re liberated to be unapologetically you.

There’s also no real room for embarrassment or feelings of inadequacy because if you’re being openly vulnerable to begin with, if you’re already super open about your fear of spiders for example and mock yourself, no one else can really ever hurt you and make you feel embarrassed about that fear.

Embarrassment comes from when you care about what people might think if they found something out about you. If you’ve already voluntarily told them that thing however, there’s nothing you can really be embarrassed about.

Using humour is always a great way to transcend any problem you might be experiencing; making a joke about a problem or fear you have is the ultimate sign that you’ve acknowledged that problem, are comfortable about it and have risen above it. As Seneca said:

“Laugher and a lot of it is the right response to things that drive us to tears”

Anger

Anger and aggression are two emotions that children, boys especially, are actively encouraged to repress. Whenever a child displays any sign of anger, they’re immediately reprimanded by their parents or teachers, subconsciously told that these natural emotions they’re feeling are wrong and that they shouldn’t feel them.

Now I’m not saying a kid shouldn’t get told off for slapping another kid in the face. But the question is: is encouraging a child to repress anger the best way of dealing with the problem? Or should we instead be teaching that anger is a perfectly normal and valid emotion but just one that we need to learn to deal better with?

As I’ve said about three thousand times already, the more you repress an emotion, the worse it’ll be for you in the future. That emotion will come back stronger and more powerful and even if it means that the kid doesn’t actively express anger when they are older, instead of that being because they are in control of it, it’ll be because they are bottling it up. And that bottling up could easily manifest in other negative forms, anxiety, depression or addiction for example.

If you’re someone who experiences anger frequently, attempting to simply wave the emotion away may not be the optimal solution. You might need to learn to channel that aggression. Whether it be going for a run or hitting the gym, there are loads of ways to healthily release that built up testosterone and aggression.

Repressing it and allowing it to build up until the point you snap is unhealthy. You want to be in control of the anger; you don’t want the anger to be in control of you.

A Buddhist practise that might help you to deal with anger is as follows:

- Whenever you feel anger arising, say: “I know that I’m angry now”

- Breathe deeply and as you breathe out say: “I send compassion towards the anger”

- Remember that this emotion will pass, the anger will soon fade

- Continue breathing in and out, considering how best, if at all, to respond

How stoicism proposes we deal with emotions

Stoic philosophy poses a similar idea to ACT when it comes to emotional regulation. As Marcus Aurelius puts it:

“You have power over your mind – not outside events. Realize this, and you will find strength.”

Too often, we allow things that happen to us, things that are beyond our control, to spark rage or sadness or distress. Stoicism proposes that we draw a kind of imaginary line. There are things in this world that you can control and there are things you cannot. The only two things that are under your control: your thoughts (the rational ones [not the subconscious roommate]) and your actions.

Nothing else is in your control. So when something bad happens, it can be very useful to acknowledge just which side of the line this happening falls on. Is this something that was brought about because of your thoughts and actions or was it something that you were not in control of?

There is no point losing your emotional stability over things that you could do nothing to change. Whatever bad thing has happened, as Russ Harris puts it:

“Accept it. Take effective action to improve it.”

There’s no point getting mad about what happened; all you can do now is use your thoughts and actions to make things better. When we experience mild to moderate pain for example, it can be easy to allow anger and rage to get the upper-hand.

But rather than continuously complaining about the pain (assuming you haven’t broken your leg or something), it’d be better if you acknowledged that nothing you say or do will change the amount of pain you’re in and so complaining or acting out is pointless.

By continuing to tell yourself that ‘it hurts so bad’ or ‘I’m in so much pain’, you’re only reinforcing the idea to your brain that it really does hurt that bad, thus exacerbating whatever pain you might be feeling.

Instead it’s better to try and experience pain as simply raw sensations in your body, chemical signals. As Marcus Aurelius recommends, when you experience pain, a way to avoid getting mad is instead of saying, “It is my bad luck that this has happened to me,” say:

“It is my good luck that, although this has happened to me, I can bear it without pain, neither crushed by the present nor fearful of the future”

The idea is that it makes little sense to see more misfortune in the event than good fortune in your ability to bear it.

Helping others

Emotions are complex and powerful and easily concealable. But that means that if a close friend is struggling, you may never know. Since emotional disguise is so easy, when someone is hurting like crazy on the inside, a lot of the time we can’t help. We can’t help if we don’t know.

So two things:

1) If on the inside you are feeling bad, don’t keep it to yourself, don’t leave those emotions to fester and slowly eat away at you. Confide. Even if there is no one in your life who you feel comfortable confiding in, there are plenty of anonymous helplines or online chat forums out there which you can turn to.

2) If you feel as though a friend is acting differently or notice that someone is alone a lot of the time or might be struggling, make the effort to speak to them. I guarantee that most people will really appreciate that someone made the effort with them.

But please bear in mind that some people are more conservative, more private and so it might take more time for them to open up to you. You need to establish trust and part of doing this is by confiding in them too. It’s a two way street. You both help each other.

Remember that you need to care about you too

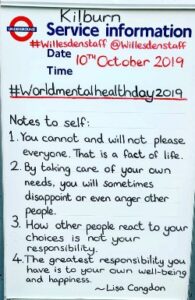

Above all, when it comes to regulating emotion, despite the fact that you should be willing to help others, you should always ensure that you are being kind to yourself too. You should never completely deprive yourself of happiness just to try and make everyone around you happy. However hard you try, you never will. So while you’re being kind to others, always make sure you’re attending to your own needs too.

Robin Williams – “I think the saddest people always try their hardest to make people happy, because they know what it’s like to feel absolutely worthless and they don’t want anyone else to feel like that.”