Does money really buy happiness?

(≈11 min read)

Zig Ziglar – “Money will buy you a bed, but not a good night’s sleep, a house but not a home, a companion but not a friend.”

In 1978 a study was published that suggested quadriplegics (people affected by paralysis of all four limbs) were more content in their everyday activities than recent lottery winners. Think about this for a second – people deprived of something most of us take for granted, use of both their arms and legs, were on average more content than people who’d won millions of pounds and had their entire lives financially sorted.

Although the study is fairly old, the results are still striking and an indication that this ‘money buys happiness’ ideology that so many of us live by might not tell the entire story.

In another study by Dr Robert Biswas-Diener, an expert on the science of happiness, similar results were found. In the study, the wellbeing of slum dwellers in Calcutta was compared to the wellbeing of the American homeless. Although both are poor, it’s well documented that the American homeless have relatively easy access to shelter, free food, coats and hygiene products whereas the Calcutta slum dwellers own virtually no possessions, are forced to endure harsh weather conditions and struggle to access basic health care, clean water and nourishing food. But despite these radical differences in wealth, it was found that the homeless in America reported lower levels of subjective well-being than the pavement dwellers in Calcutta.

The question is then: what other factors were at play? And what things can we practise in our own daily lives to improve the odds of us finding more joy in everyday activities? Can money really buy happiness?

What things do we need to be happy?

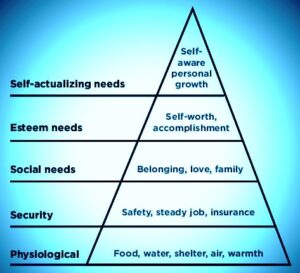

When it comes to investigating the relationship between money and overall wellbeing, Maslow’s hierarchy provides a great foundation.

Maslow suggests that human beings are motivated by a set of underlying needs. These range from basic needs which include food, water and shelter placed at the bottom of the hierarchy to self-awareness and personal growth placed at the top. Maslow initially proposed that we could only move on to acquiring the next set of needs once we had met the previous set but as I’ll later mention, this might not quite be accurate.

The reason the hierarchy holds so much value is because it suggests that contentment and overall wellbeing might not be intrinsically tied to money, and factors such as social needs and personal growth might be more important contributors.

For example, in the ‘security’ row, Maslow suggests that all we need is a ‘steady job’. The row above then has no mention of more money but rather suggests the next most important thing is our social needs. Research based on over 450,000 responses from people in the US suggested that:

“Emotional well-being also rises with log income, but there is no further progress beyond an annual income of ~$75,000.”

The research supports Maslow’s hierarchy and suggests that once people have met their basic needs and are financially secure, money has little to no impact on emotional well-being.

But wait. The hierarchy may not be as rigid as it might appear. In his original 1943 paper, Maslow suggested that only when one set of needs were met, that you could move up the hierarchy and focus on the next set of needs, but later pointed out in a 1987 paper that he may have given “the false impression that a need must be satisfied 100 percent before the next need emerges”. In this way, the needs can be seen as somewhat flexible based on external circumstances or individual differences.

In a study published in 2011, researchers from the University of Illinois put the hierarchy to the test.

They found that while the fulfilment of the needs was strongly correlated with happiness, people from all over the world reported that self-actualization and social needs were important even when many of the most basic needs were unfulfilled.

The results suggest that while the needs Maslow noted may be strong motivators of human behaviour, they do not necessarily take the hierarchical form Maslow described. In fact, as I’ll now discuss, a large body of research actually suggests that social needs might be the most important when it comes to contentment.

The importance of social needs

Earlier I mentioned the study conducted by Robert Biswas Diener on the slum dwellers in Calcutta which found they had higher levels of subjective wellbeing in relation to the American homeless who have much greater access to ‘basic needs’ like food and shelter. Diener goes on to give an explanation for this result:

“A closer look at the data showed that a large part of the relative life satisfaction of the Calcutta sample was due to the pavement dwellers’ high quality social relationships; cultural and economic factors doom many Indians to collective poverty with their families, while many American homeless people are often estranged from their friends and loved ones.”

This explanation seems to contradict Maslow’s hierarchy in that social needs are being used to compensate for basic needs. So how important then are social needs, when it comes to contentment?

A study conducted by the Harvard Study of Adult Development followed the lives of 724 men placed in two groups for a period of 75 years to find factors that could increase the odds of living a happy and healthy life. (I know I’m referencing like eight thousand studies, but I really want this article to be as objective as possible. As always, if you disagree, want to discuss things, or want to insult me, feel free to contact me via twitter.)

Robert Waldinger, director of the study, said in a TED talk:

“When we gathered together everything we knew about them about at age 50, it wasn’t their middle-age cholesterol levels that predicted how they were going to grow old. It was how satisfied they were in their relationships. The people who were the most satisfied in their relationships at age 50 were the healthiest at age 80.”

In the research paper produced by Diener, similar conclusions were drawn:

“Having intimate, trusting social relationships appears to be necessary for happiness. Comparisons of the happiest and least happy people show that the dimension in which the happiest people are similar is having high-quality friendships, family support, or romantic relationships; the happiest folks all had strong social attachments.”

Clearly then, when it comes to wellbeing, money is not the be all and end all. There are numerous factors that can influence how happy someone is and there’s sadly no magic formula or equation that’s applicable to us all. Your own personal needs and what makes you happy is fairly likely to differ from what makes someone else happy.

It’s worth noting, however, that when I refer to happiness, I’m not referring to that feeling you’d get if you were to take a boatload of drugs. I’m referring to long lasting happiness, what some may regard as contentment. This might sound like nonsense, but happiness, in isolation, is actually an incredibly dangerous thing to strive for. Why? Well because happiness is a fleeting emotion, just like anger or disappointment, that comes and goes arbitrarily. If temporary pleasure was the measure of happiness, drug users would be amongst the happiest people on Earth.

Whenever I make the argument that money has little bearing on happiness, there are always those people who respond by telling me how buying that new cricket bat or that chocolate cake made them happy.

The problem with this argument is that whatever it is you buy (apart from maybe a dog), you’ll get accustomed to. Any item, used for long enough, will lose its novelty. That initial rush of euphoria will leave you. And how might you get it back? Well, perhaps through another purchase. And when you get accustomed to that purchase, perhaps you buy another. The cycle perpetuates. This process is known as hedonic adaptation.

The problem with predicating our emotional wellbeing on purchases that induce instant gratification is the risk of us becoming reliant on temporary pleasure to sustain us and addiction manifesting as a consequence. Rather than becoming reliant on short term pleasure, living with meaning and establishing a long term purpose is arguably a much better alternative. Although buying things can help you feel short-term happiness, it certainly won’t benefit you in the long run.

In the remainder of the article, I’m going to run through two techniques I personally use which science has also found to improve the odds of overall contentment.

Gratitude

The fact of the matter is this: to even be able to consider the meaning of life renders you ridiculously fortunate. Over the past a thousand years on Earth and still in much of the world today, the ‘purpose of life’ is predefined upon birth. Survival.

Restricted access to drinking water, working twelve hour days to provide the bare minimum amount of food to sustain the family, compelled to engage in sex work just to have a bed to sleep in, fear of being sentenced to death or tortured for speaking the wrong words – this is the harsh reality much of the global population faces daily.

So when contemplating what it takes to be happy, it’s vitally important to first acknowledge your immense fortune. There are millions of people in the world today who, if you were to tell them about your life, would think you were living in some kind of form of heaven. They’d consider their dreams made if they could spend a week, even a day, living in your shoes. You therefore, to millions of people out there, are already living the dream life.

Gratitude has been shown by a large body of psychological research to be an effective approach to maximising contentment. Here are several ways you might go about practising it.

Volunteering

Gratitude and volunteering are somewhat intrinsically tied to one another. The more you volunteer, the more grateful you become of what you have. Once you experience first-hand what other people in the world must endure and learn to live with on a daily basis you naturally begin to feel blessed that you have the life you have.

You’re compelled to consider just how lucky you are not to have been born into poverty or without certain limbs or disabled or with certain mental disorders or with abusive family members. Things that you’d ordinarily take for granted, like sight for example, you suddenly feel extremely appreciative about.

The truth is, if not for an accident of birth you could be easily be the people you are volunteering to help. And as I mentioned earlier, to them, you are already living the dream life. Learning to be appreciative of that fact is paramount to feeling content with where you are. Volunteering can help open your eyes to the real world and help you to realise just how lucky you are.

Using a diary

Unfortunately gratitude is not something that you can learn overnight. It takes time. But it’s still something that’s completely attainable when practised daily. One thing you might do for example is use a diary.

“Every night, write three things you encountered during the day that you are grateful for.”

I’m fully aware that this might seem like a tonne of work, but the more you do it, the more you’ll begin to experience the benefits. With time, as you go about your day to day business, instead of blindly partaking in various experiences, you might start noticing that during the day you’re always on the lookout for anything you might be able to write in your diary. You are, in a sense, training your brain to automatically search for things to be grateful for.

Some people find that instilling gratitude into their wake up routine can be useful too. For so many of us, we feel a compulsion to wake up and instantly check our phone, that flood of bulletins darting into our minds and inducing stress before our minds even have a chance to properly awaken.

To bypass this problem, you might instead create a routine that involves mentally running through a list of things that you’ll likely encounter in the day ahead that you’ll be grateful for. The advantage of practising gratitude in the morning is that it could put you in a better mood for the day ahead. You do however miss out on the benefits of reflecting on the day that’s just gone.

There are hundreds of gratitude diaries online that you can buy to help you with your routine, but from my experience, if you’d prefer to save a little money, a simple notepad will do the trick.

Negative visualisation

As well as creating routines that encourage us to feel gratitude, there are also things you can do during the day, when perhaps you’re feeling down or angry, to elevate your mood.

A technique used in stoic philosophy to help us feel gratitude is as follows:

Whenever you find yourself stressed or angry or sad, for example if you’re stuck in traffic on your way to work, take a moment to think about all the bad things that could have happened to you that haven’t.

The person who you most love could have been stripped away from you today. You could have been diagnosed with terminal cancer today. You could have had a sudden heart attack today and been paralysed from chest down. You could have been diagnosed with motor neurone disease today.

Now if any of those things would have happened, how much would you be willing to pay, to get back into the exact moment you find yourself in right now? You’d consider your prayers answered if you could simply return to this moment.

Considering these things puts life into perspective – is you being late to work really the end of the world? I mean, yes, being yelled at by your boss is pretty bad, but your life could be much much worse.

Something to bear in mind when practising gratitude

Although practising gratitude is on the whole, overwhelmingly positive, there is one point that’s important to mention:

“Don’t trivialise your own problems.”

Just because someone, in another part of the world has a ‘worse’ problem than you, that doesn’t mean your problem is irrelevant. Your problem is just as valid as theirs. Your problem is real and still needs to be fixed.

Gratitude does not mean you are not allowed to feel sad. Being sad is perfectly ok and normal and like any other emotion, it’s something that will pass. By attempting to repress that sadness and pretend it doesn’t exist, you are doing yourself a disservice. The more you try suppressing an emotion, the harder it will bite back later down the line.

The idea of gratitude is not to contrast your life with people in worse conditions and simply view all your problems as irrelevant but instead to look into your own life and think about the things that you take for granted that you should probably be extremely grateful for.

Rather than focusing on the problems you are experiencing and the negativity in life, focus instead of the positives, on what there is in your life and how lucky and blessed you are to have these things.

It is perfectly plausible and possible to acknowledge that you are sad but nonetheless feel grateful simultaneously.

Prabhugi – “Happiness is not to desire what you do not possess, but to appreciate what you already have.”

Mindfulness

Mindfulness is a fairly new phenomenon, and something that’s slowly taking a hold of western society. Numerous scientific and psychological studies are in all agreement with the idea that mindfulness can have significant benefits for our mental health.

Research by Hofmann et al. who analysed 39 studies on mindfulness, found their results supported the use of MBT (mindfulness based therapy) for mental disorders such as anxiety and depression. Other research has suggested mindfulness can have benefits for sleep, chronic pain, our immune system and our brain.

For a more detailed guide of the different kinds of mindfulness techniques you could use, feel free to check out my more detailed article, but for now, I’m going to present one of my favourites and talk about how you might implement it in your daily life.

But to begin with, what even is mindfulness?

What is mindfulness?

We, as humans, experience a great degree of psychological pain through either intense rumination about the past or intense worry about the future.

Mindfulness teaches us how to better access the present, to live free from the burden of the past or the future. To observe the world in all its beauty without our prejudices, opinions and beliefs interfering can be a surprisingly wonderful thing. Learning to have a heightened sense of awareness about the world also enables you to have a heightened sense of awareness of yourself.

As well as the numerous mental and physical health benefits I’ve already mentioned, mindfulness can help you to see the world in a more clear and colourful way.

How to practise mindfulness

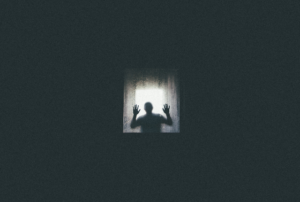

Ultimately, mindfulness can be practised anywhere, but I’ve found from personal experience that it’s much easier to practise alone. You could practise it when you’re out for a walk, when you’re staring out your bedroom window or even just sitting comfortably in bed.

The basic aim of mindfulness is for you to become increasingly aware of your surroundings and the sensations on the different parts of your body in context with that surrounding.

Let’s say for example you’ve gone for a walk. Instead of thinking about why drunk vegetarian you ate fish and chips last night or that horrible meeting you had earlier today, bring your awareness to the here and now. Run through each sense, asking yourself questions:

How does the wind feel against your skin? How does your skin feel against the texture of your t-shirt or socks or trousers? What sensations can you feel in your body when you breathe in the air? Is it cold or warm? Become aware of your breath, of the air hitting the back of your throat and filling your stomach – how does that feel?

What noises can you hear? The sound of cars? Of trees waving in the wind? Of a couple arguing? Of birds singing? Pay close attention.

What can you smell? Freshly cut grass? Litter? Dog excrement? Don’t attach an opinion to that smell. Just simply observe. Inhale through your nose and be aware. Being aware means there is no reaction, just observation.

Look around you. Just observe. What kind of things can you see? The trees waving? The ripples in a puddle? The moon in the sky? A kid hugging a lamppost? Just watch. If a thought arises, that’s ok. Don’t try and push it away. Just be aware of its presence and sit with it until it passes.

There’s this widespread view that meditation is somehow the act of ‘not thinking’. As peaceful as that sounds, meditation is not control of thought or even suppression of thought. As Jiddu Krishnamurti says in his book ‘Freedom from the known’:

“Meditation is to be aware of every thought and of every feeling, never to say it is right or wrong but just to watch it and move with it.”

And goes on to say:

“Meditation is a state of mind which looks at everything with complete attention, totally, not just parts of it.”

When you are being mindful, you are devoting your complete attention to the here and now; your mind has emptied itself of the past and the possible future.

Some people initially find it easier to practise mindfulness under the guidance of a voice. There are plenty of guided mindfulness YouTube videos online and if you feel they might benefit you, I’d recommend trying out various channels until you settle on a voice you feel the most comfortable with.

The ultimate idea of mindfulness is, to outline a Buddhist idea, for your thoughts “to become like robbers in an empty house”. They cannot affect you or hurt you or take anything away from you.

You should instead view your thoughts as a kind of consistent and constant background radio noise that you can choose whether or not to pay attention to. You can tune in for the helpful thoughts and just allow that blur to continue for the unhelpful ones.

Meditation, mindfulness and becoming simply aware of thoughts as opposed to trying to repress them or allowing them to control you can all help in this journey to improved contentment.

You’re already enough

To end, a quote from my favourite existentialist, Albert Camus:

“You will never be happy if you continue to search for what happiness consists of. You will never live if you are looking for the meaning of life.”

The truth is it’d actually be pretty easy to waste your entire life away desperately searching for how to be happy. The reason – there is no concrete answer. You’ll never know for certain what makes you happy and your search could continue forever. But the more you search, the more you’re missing out on life itself.

There’ll always be a gap between what you have and what you want and this gap will make you unhappy. But that gap will never close. No matter how much you have, it’s human nature to always want more. The urge to want things doesn’t stop when you reach the things you previously wanted; you’ll just come up with new things you need.

This means, if you’re not careful, you’ll spend your entire life climbing a mountain that never ends. You’ll tell yourself that when you reach the summit, happiness will finally arrive. But in reality, the summit doesn’t even exist; every time you think you’ve reached it, you’ll see an even higher peak in the distance.

So sometimes, instead of agonising over what you are missing that would make you happy, it can be useful to take a step back and remember that when you love what you have, you have everything you need.

Happiness is a state, a temporary state that comes and goes. Ultimately therefore, you can’t pursue happiness. Your goal in life cannot be ‘to be happy’. Why? Well because:

You can’t pursue what should be a side effect of other pursuits.

As Thich Nhat Hanh said:

“There is no way to happiness. Happiness is the way.”