Death – a brief guide on how to view it

(≈14 min read)

Christopher Hitchens – “It will happen to all of us that at some point you’ll be tapped on the shoulder and told, not just that the party’s over, but slightly worse: the party’s going on, and you have to leave.”

Death is one of those topics that a lot of us are reluctant to talk about; a mysterious and discomforting fact of life we keep locked firmly away in the back of our minds. It’s my belief, however, that deep consideration of death can actually serve to reshape, in a positive way, how we live life in the present.

At this point, you might be wondering how reading about death could possibly help you. You might also be wondering if it’s normal for a young guy to devote multiple hours of his time writing an article on death, and I can assure you, it’s certainly not. But hear me out – let me explain to you why thinking about death can change your outlook on life.

Ernest Becker, in his incredibly dense, but exceptionally interesting novel ‘Denial of Death’, argues that there exists this tendency in us all to deny death. Whether that be believing in an afterlife, striving for fame so we’re remembered after we die, deluding ourselves into thinking that our children will carry a part of us on in the future or storing endless photos that’ll exist forever, Becker asserts that it’s human nature to try and transcend mortality.

But why? Well, for many of us, we’re not actually afraid of death itself. We fear death because we fear the unknown, and death represents the greatest unknown of all. Realistically lightning could strike at any time. Any moment, and the one life you have…gone…forever.

No one’s immune from that crazy drunk driver or that customary ludicrous death on the weekly news. But our brains convince us otherwise. As Becker points out, this proclivity is most noticeable in soldiers. Every soldier deep down feels sorry only for the man next to him who will die. As Becker says:

“Each protects himself in his fantasy until the shock that he is bleeding.”

I firmly believe that acknowledging life’s finitude and our impermanence is actually a key part of living a more meaningful life. To truly accept the undeniable fact that you will die is to finally start living.

Why acknowledging your mortality can lead to a better life

To start, I want you to consider that as you’re reading this right now, there is a clock, a countdown that’s constantly ticking away. You don’t know what it’s set to. You don’t how long you’ve got. But it’s there. And when it hits 0, everything you know, everything around you, everyone you love, will disappear forever.

You might die tomorrow. You might die in a week, in a month, in a year, in a hundred years. Regardless of when, it’s going to happen.

And that fact in itself can genuinely revolutionise how you view time. Time is not a commodity. It’s precious and you don’t have an unlimited supply of it. Every day that passes is a day you’ll never get back.

With that in mind, it becomes pretty clear that wasting this one life you have seems somewhat nonsensical.

Life’s just too damn short to let it fizzle away and realise only on your deathbed that you didn’t live fully. Before you know it, it’s all going to be over…everything you know and love… gone. Why then would you voluntarily waste the one life you’ve been blessed with living somebody else’s life?

The futility of fame

But just because we should make the most out of the time we have, that’s not to say we have to do something great for our life to have meaning. A meaningful life doesn’t have to involve fame or obscene wealth.

The way I see it, people live so they can make cake and fall in love and go to concerts and watch their kids grow and surround themselves with the people that make them happy. All the little things are really the big things because they are what make you you.

Being grateful for what you have, getting out of bed each day, despite knowing you are going to be faced with adversity and trying and trying even when faced with failure, are all far more important than fame and achievement when it comes to contentment.

Fame and wealth both disappear upon death. In a short time the entire memory of you will be gone from earth forever, like you never even existed. In my eyes, it’s better to focus on living fully in this life; whether that be through pursuing a career you love and working hard at it, even if it doesn’t bring you wealth or enjoying the little things, rather than striving for immortality through fame or money.

Death is the end. All you have is this time on earth; how you are viewed or remembered after death should be of little concern to you. Perhaps instead of denying the idea of death, we should embrace it and use it to decide how we want to live.

A helpful analogy

Let me give you an analogy to make things even clearer:

Imagine you’re playing a game of football. But there’s one rule: the referee can choose to end the game at any moment. Sounds like an awful rule, I know, but how does this one rule change things?

Well, now you have two options:

You can

1) Play but with a constant worry that the game is going to end

Or

2) You can simply choose to enjoy the time you have playing until it’s over

Call me crazy, but I’d say option 2) sounds a lot more appealing. The same is true in life. When you really start to appreciate this fact, you’ll begin to realise just how pointless some of the things that you direct your energy towards really are.

Let’s use a common example – road rage. Say you’re driving and someone in front of you stops suddenly. The natural reaction for most of us is to allow this wave of complete fury to seize us, bubble up to the surface of our skin, and then release itself in the form of verbal abuse, swearing to ourselves about a complete stranger. Swearing about someone we’ve never seen, about someone we know nothing about.

But what if you took a moment to stop and think:

“This person in the car ahead of me is going to die soon. In fact, so am I and so are all the people we both love. I don’t know what’s going on in this person’s life, their family situation, their job, their mental state and maybe if I did I’d feel a huge amount of compassion. All I know is that they made a mistake on the road. Perhaps this person is trying the best they can in the circumstances they are in, just like me. What does anger really achieve other than diverting my attention away from the meaningful conversation I was having with my wife in my own car in order to get mad at some stranger? Will getting angry actually achieve anything, change anything?”

Obviously reciting this word for word every time someone does something stupid on the road would be, in itself, a fairly crazy thing to do. But the point I’m trying to make is that instead of thinking about how awful and morally inferior this person is, it might be more beneficial to instead acknowledge that you’re just two mortal beings driving on some random road in infinite space, two beings that’ll soon no longer exist.

Marcus Aurelius – “The closer to control of emotion, the closer to power. Anger is as much a sign of weakness as is pain. Both have been wounded, and have surrendered.”

But in the grand scheme of things…

When we talk about death, there’s a strong susceptibility to think ‘in the grand scheme of things’. The problem is, the more we contemplate and ruminate about death, the deeper and deeper we can find ourselves plummeting until eventually we’re left wondering what the point of anything is. If death washes away everything you’ll ever achieve, then what’s the point in achievement? What’s the point in anything?

In the grand scheme of things, there’ll come a time when every single one of the seven billion people currently living on earth will be dead and replaced with an entire new generation.

Think about that for a second. Everyone you see today will soon die. And you’ll never know anything about anyone. Every day you walk past people, oblivious to their lives, their passions, their hobbies, their interests; all this complexity that’ll soon be sucked into a black hole and forgotten for eternity.

We all stick to our own little confined bubble until eventually that bubble bursts and we are wiped off the surface of this planet and forgotten. In the grand scheme of things, people will continue living for millions of years to come. Your death will essentially be an irrelevance, a minute cosmic blip. It’s inevitable that you’ll soon become a distant memory, a line on a grave that no one visits, a corpse rotting away, while the earth carries on spinning.

But even if all that’s true, is it exactly helpful to consider? With this question in mind, it becomes increasingly obvious why people believe in an afterlife – the repercussions of facing the reality of mortality and life’s finitude is a huge burden to bear. But is belief in an afterlife really the right way to bear this burden?

The problem with an afterlife

Let’s imagine for a second that we could live forever and that, assuming we were moderately good people, would find ourselves in some form of ethereal, blissful heaven come death.

If you could get away with being only minimally good and scraping into the same heaven as someone who was unwaveringly good it would be illogical. That’s why most religions outline the idea that the better person you are in this life, the better heaven you’ll get into. For the sake of argument, let’s imagine this to be the case.

So let’s imagine that when we die, we get to spend the rest of time, a blessed eternity, experiencing this perpetual pleasure in heaven. What does that mean for us right now, on this earth, in this present life we are living?

Let’s begin with an analogy. If you had a hundred trillion pounds, what would a hundred pounds mean to you?

Well…nothing. A hundred in comparison to a hundred trillion is meaningless, insignificant.

But if heaven existed, and we could never truly ‘die’, it follows that we’d spend an infinity of time there.

Now let’s now compare this a hundred trillion years plus in heaven to this comparatively tiny amount of time you have on earth – maybe a hundred years if you’re lucky. Compared to this eternity of time in heaven, it’s pretty clear that a hundred years is virtually nothing and it almost renders your entire life meaningless.

Well, not exactly meaningless. If you truly believe in heaven and the idea that you’ll never die, you should really be using this comparatively tiny space of time that is your life to ensure you’ll get into the best version of heaven possible. That, according to most religions, is where you’re going to spend the majority of your time, so doing anything other than this would be nonsensical.

You should join a monastery or become a religious leader or do anything remotely possible to get into that highest level of heaven possible and so experience the maximal level of joy forever. The life you are living right now – that’s secondary.

This is where I have a slight issue. I personally believe that death is the end. And I tailor my life in accordance to this fact. I know that if I want to do something, I only have this life to do it and so it’s essential I leave nothing undone.

Belief in eternal life compels you to devote a huge amount of time trying to get to a place you don’t know objectively exists. And for me, depriving someone of this life, the only thing we know for certain exists, in return for the possibility of eternity is, in my opinion, questionable.

Why the finitude of life makes life more meaningful

If you kiss your child goodnight for the last time, it’s important for you to recognise that that might be the last time you ever kiss them. Not thinking this because you believe you’re going to somehow meet again in the afterlife is, in my eyes, somewhat problematic.

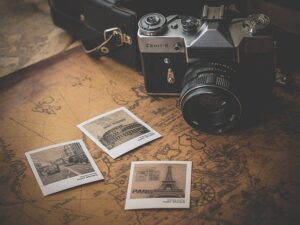

Dr Piers Steel, author and economics professor, devised the following formula for productivity:

If you want to learn more, check out his book, ‘The productivity equation’, but for now I just want to focus on the variable ‘delay’. Steel suggests that the longer we have to complete a task, the less motivated we will be to complete it. That explains why, for example, you’re much less likely to complete that assignment a week before the deadline in comparison to the night before.

But let’s think about what the repercussions of this formula might be, for example, if an afterlife existed. If time was infinite, you’d have an infinite amount of time to do anything you’d ever want.

As ‘delay’ in the equation tends to infinity, motivation would simultaneously tend to zero. You’d lack motivation to do anything meaningful because there’d always be an infinite amount of time to do it. The whole reason anything in life actually means something is because one day you’re going to get old and die and never get to experience that thing again.

If we were able to do things over and over forever, we would lose appreciation for them entirely. It’s the finitude of life; the fact that everything comes to end that motivates us to do painful things.

The procrastination that would ensue if life was infinite would be immeasurable – we could always do that painful activity tomorrow.

Imagine for example the difference between an average person eating a meal and a prisoner eating that same meal but knowing it is their last. How might the experience differ for each person? Who would appreciate the food more and be more present whilst eating? Clearly, the idea of finitude, of time being finite, is what makes things meaningful.

In my article, ‘How to stay motivated while pursuing your dream’, I discuss the ‘last time’ technique.

Every time you are about to engage in an activity, let’s say for example going to the gym, remind of yourself of two things, two true facts:

- That there will be a last time you ever do this activity

And:

- That there is a possibility that this time, right now, is the last time you will ever do this activity

For all you know, tomorrow you might be involved in a terrible accident or be diagnosed with a certain kind of illness that strips your ability to move as you currently do. This time in the gym may very well be your last. Now take a moment to think about how this consideration might change your workout.

I know it’s not exactly pleasant to remind yourself of the fact that one day your capability for physical movement will vanish and that you don’t know when that day will come but this thought is what helps us to motivate ourselves to do anything. If life was infinite, this life would simultaneously be rendered almost meaningless.

When considering something as deep as death, I personally find thought experiments like the one above, helpful (and weirdly entertaining). Here are three more of my favourites.

The deathbed thought experiment

Imagine you’re on your deathbed. You can feel yourself drifting away, your body getting lighter. It’s going to end; you can feel it. And soon.

What kind of thoughts are whirring through your mind? What are you thinking about? Who are you thinking about?

I’d encourage you to a set aside an hour or two to really commit to these questions. Close your eyes and immerse yourself in the scenario. When that moment comes, imagine how your body might feel, how your mind might feel. Who and what are you thinking about?

Shockingly, I’m not asking you to ask these questions to yourself to scare you, but instead to help you to establish what things in life you truly value.

The likelihood is, on your deathbed, you’re not going to be thinking about your annoying work colleague or that annoying fox which keeps excreting on your lawn. Chances are you’re going to be thinking about things and people you truly love, people who have enriched your life in the best way possible.

By establishing who exactly these people are in your own life right now, you can place less weight on trivial meaningless things, like family feuds or whether to pick the red sofa or the black one and instead prioritise the things and people in life that are worth it.

On your deathbed, the one thing you don’t want to feel is regret. You want to look back and know that there was nothing more you wanted or could have done.

You can make that happen. Right now. What things are holding you back? What things do you need to change in order to help you feel more content?

If you know for a fact you’ll perish and be washed away, that thought should in theory, motivate you right now, in this moment, to take control of your life and make the most out of it. (The key words there being, ‘in theory’.)

Who cares if you get rejected? Who cares if they say no? Who cares if they think you’re stupid? What’s the point in spending so much time consumed by thoughts about what others think of you when you’re both going to be dead, distant memories, soon anyway?

You’ll soon be gone and the more you accept that, the more meaningful your life can become. Make the most out of the time you have, and don’t waste it ruminating about stuff that when you’re on your deathbed will seem nothing but irrelevant.

Funeral thought experiment

Imagine that you were to die in the next five seconds. Difficult to imagine, I know, considering that by the time you’ve finished this sentence, you’re presumably still alive. Now imagine once you died, you became an invisible spirit in the world. But you could only stay and observe the world for a day, the day of your funeral.

I want you to imagine who’s there, standing around the casket. Who’s giving eulogies?

What do they say about you? What kind of person do they describe you as? How do they describe your life?

Again, really try and immerse yourself in the scenario, imagine what the people who love you most might say about you.

What kind of person were you to them? What kind of things did you do specifically that improved their lives? What other things would they say about you?

After spending a while honestly answering all these questions, take a step back, look at your life right now and ask yourself: is what I’m doing now lined up with what I would want them to remember me for?

What things can you do right now, what steps can you take to adjust your life to be more like the one you painted out in this vision?

The illness thought experiment

Imagine tomorrow you were diagnosed with a terminal form of cancer. You know you’re going to die and you need to figure out what to do with the brief time you have left before you go. What kind of things would you do? What experiences would you want to live?

Once you’ve given these questions thought, it’s important to realise that the responses you give are equally applicable to your current life. The fact of the matter is this: life is a kind of terminal illness.

And by treating it this way, it reduces the odds of you getting sucked into the seemingly inescapable way of living that most feel there is no way out of – chasing money and wasting life away working a meaningless job.

Would you really care about accumulating money if you were diagnosed with that terminal illness? Or would things like family, love, kindness and meaning be more important to you?

By viewing life as nothing more than this illness that could take you at any time, you are simultaneously acknowledging the fact that you are mortal. And this acknowledgement can help clarify what things in life you truly value.

When the philosopher and author Christopher Hitchens, who’d been diagnosed with cancer, was asked how he was feeling at the end of a public debate, his response was:

“I’m dying…but so are you.”

Grief

Robin Williams in the film, ‘Good Will Hunting’ says to Will:

“You don’t know about real loss, ’cause it only occurs when you’ve loved something more than you love yourself.”

For a lot of us, the saddest part of life is when the person who gave us the best memories becomes a memory.

When talking about grief it can often be useful to consider this thought experiment:

Imagine there was a pill that could immediately remove any feelings of grief completely – when, if at all, would you take it?

Of course, almost no one would take it right away. If you witnessed your child get run over and die, you could simply take this pill and ten minutes later, go shopping, have a coffee and go about your day like nothing happened. Clearly, that’s not something most of us would actually want. We kind of want to feel pain.

It’s somewhat contradictory but suffering is a necessary component of grieving and if we had the choice a lot of us would actually choose, despite the fact this person we love is gone, to continue suffering and reliving those memories because to not do so would feel like we’re being somewhat ungrateful for the impact this person has had on our life.

Grief is perfectly normal and natural. When you lose someone you love, a part of you wants to remember that person, to hold onto, cherish those happy memories you hold so dear.

You’ll never get the same moment twice and so memories can provide a way of reliving old times. But when we summon these memories excessively, reliving them can begin to feel painful. Each and every photo or video that you see reminds you that these are memories you’ll never again recreate.

They remind you that you’ll never again be able to write new memories with the person you’ve lost. But a part of us has to hold on; we can’t simply expunge all those parts of someone we hold so close to our heart. It’s just about moderation and not sentencing yourself to extra unnecessary suffering.

Presumably that person you loved would want nothing more than for you to make the most out of your life, rather than sentence yourself to perpetual torture thinking about them.

Grief is inevitable and natural and healthy but if it becomes paralysing to you for a significant period of time, it might be time to see a psychologist or another mental health specialist who can offer individualised support.

A question to help shape your life

Victor Frankl’s ‘Man’s search for meaning’, opens by outlining a question he, as a psychiatrist would ask his patients. It’s an incredibly useful question that can be thought through by anyone.

“Why do you not commit suicide?”

I know you might think I’m crazy and the question might appear rather sinister and dark, but deep consideration of the answer can highlight what things in life you truly find meaningful. The most common response might be ‘my family’. In which case, you have highlighted something that gives your life meaning. For others it might be that novel they are working on or the dream of living out in the mountains or the prospect of having children or even their children themselves.

Whatever your response might be, everything you list is guaranteed to hold a significant amount of importance in your life. The idea is to weed away the meaningless things that are you doing out of necessity and instead pinpoint what things in life are truly important to you.

As Albert Camus puts it:

“The literal meaning of life is whatever you’re doing that prevents you from killing yourself”

Dr Frankl goes onto mention that a good way to aid in the pursuit of meaning is to:

“Live as if you were living already for the second time and as if you had acted the first time as wrongly as you are about to act now”

When you live life as if you have encountered a near death experience or as if you were living your second life, it changes your perspective on things.

Considering what it might be like to be on the brink of death and somehow getting through it to survive and getting a ‘second chance’, so to speak, can make you more grateful for what you have and highlight what things are important in life. Suddenly simple things that are often taken for granted like family and nature and love might mean a whole lot more.

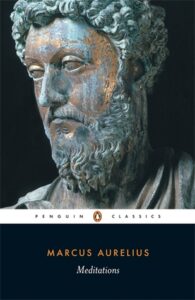

2 ways to help deal with the fear of death (from Marcus Aurelius)

Marcus Aurelius’ book, ‘Meditations‘, contains a huge amount of wisdom and is a good foundation for anyone interested in improving wellbeing from a psychological standpoint. It also includes a lot on death and learning how to view it. I’ve picked out two pieces of advice I found to be especially useful.

“Death, like birth, is a secret of nature”

When you consider death as simply a part of nature, just like birth or puberty or having a child, it reduces the burden you feel every time you think of it. Death is something that’ll just happen, regardless of circumstance or age or situation.

When it happens is undetermined and so why spend your precious time paralysed by the thought of dying young? If you die young…you die young. And when you’re dead, you won’t be missing out on anything. How can we ‘lose’ the future? We can’t be deprived of something we have never possessed.

“Both the longest-lived and the earliest to die suffer the same loss. It is the only the present moment of which either stands to be deprived.”

The person who dies at twenty suffers the same loss as the person who dies at a hundred. I know that statement might initially make absolutely no sense, but it is the only the present moment that can be stripped of us. The past, the future; we can’t lose them because we’ve either never had them or they’ve already happened.

So for that reason, it’s so important that we start trying to root our minds to the present and to an extent disregard our unavoidable fate in the future. A technique I’d recommend using to try and connect on a deeper level with the present moment – mindful meditation.

Why worry about something that you know for a fact is going to occur? It’s a waste of mental time, mental space and the time spent worrying about the future could instead be spent enjoying the present. To end, a quote:

Epicurus – “Death does not concern us, because as long as we exist, death is not here. And when it does come, we no longer exist.”